|

| John Ward |

Viral Hepatitis Prevention Coordinators (VHPCs) are vital to the implementation of the nation’s Action Plan for the Prevention, Care, & Treatment of Viral Hepatitis, and ultimately, achievement of 3 of the national goals of reducing viral hepatitis transmission and disease:

- Increase the proportion of persons who are aware of their hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection,

- Increase the proportion of persons who are aware of their hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, and

- Reduce the number of new cases of HCV infection.

Funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and positioned within state and local health departments, VHPCs serve over 50 jurisdictions around the country including 48 states and several major cities. Because each community is unique, VHPCs evaluate local data to tailor prevention activities for their jurisdictions and seek local partnerships and resources to implement these activities where they are most needed. Since the program began more than a decade ago, the coordinators have improved the effectiveness of viral hepatitis prevention activities, identifying ways to integrate viral hepatitis prevention vaccination, testing, and linkage to care within existing public health, clinical care, and community settings. A recent report on the VHPC program, “Accomplishments of the Viral Hepatitis Prevention Coordinator Initiative, 2008-2012,” outlines the program, describes the scope of activities, and highlights examples of outcomes.

The VHPCs determination and ingenuity have led to a number of successes, including:

- Identifying and addressing unmet educational needs, including supporting the translation of educational materials into myriad languages to better reach persons at risk in various jurisdictions;

- Providing technical assistance to answer questions from state policy makers about rapid HCV testing;

- Developing state and local guidelines for viral hepatitis services that support implementation of CDC recommendations, e.g., guidelines on who is offered hepatitis A and B vaccinations in public health clinics;

- Launching and managing peer-education programs in correctional settings; and

- Conducting analyses of surveillance data to better inform the allocation of limited resources and improve program impact.

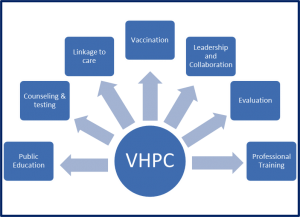

VHPCs engage in a diverse array of viral-hepatitis-related services and activities (See figure). Through community partnerships, VHPCs identify collaborations and resources that support implementing the Viral Hepatitis Action Plan at the state and local levels. One example of this is VHPCs’ preparation of resource directories that list local care facilities offering essential viral hepatitis vaccination, testing, care and treatment services. VHPCs are also educators, providing the latest information on hepatitis B and C to the public as well as diverse groups of health-care and social-service providers in their jurisdictions. Some VHPCs have developed epidemiological profiles of transmission and disease trends in their communities and used these data to engage with partners and inform the development of a strategic viral hepatitis plan for their state or city.

|

| Viral hepatitis prevention coordinator’s core activities |

VHPCs leverage opportunities to increase awareness about viral hepatitis, prioritize those activities that can make the greatest difference in the lives of individuals at risk in their jurisdiction, and coordinate with other groups to make the most of available resources. Indeed, the opportunities to promote adoption of viral hepatitis prevention services recommended by CDC and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force have never been greater, particularly given relatively recent changes in policies and technology.

CDC and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend HBV and HCV testing for similar populations. As a result of the USPSTF recommendations, HCV screening is provided as a preventive service to clients by most health plans, with no out-of-pocket expense. HBV screening will be added to the list of covered preventive services in 2015. In addition, Medicaid expansion also is increasing the number of persons with access to viral hepatitis prevention and screening services. A point-of-care test for HCV is now available, thereby increasing the types of settings in which testing can be provided; and, the widespread adoption of electronic health records provides new opportunities to remind providers of the need to test patients. Using available tools, VHPCs work in close collaboration with health-department colleagues and external health-care system partners to promote CDC and USPSTF’s recommendations for hepatitis B and C testing and linkage to care and treatment.

I encourage everyone working in the field of viral hepatitis to look for opportunities to collaborate with the VHPC in their jurisdiction. As Dan Church, VHPC in Massachusetts, states, “There is clearly much more work that remains to be done, from enhancing HCV prevention efforts among young persons who inject drugs to expanding testing and medical management services for persons with hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection. Due to the infrastructure and collaborative relationships that have been made possible through this initiative, this expanded work is more feasible.” The VHPC program is vital to the achievement of the national goals of the Viral Hepatitis Action Plan. I salute the work of the coordinators for their contributions toward developing the foundation upon which we continue to build our national response.

John Ward, MD, is the Director of the Division of Viral Hepatitis, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention This post was originally published on AIDS.gov.

Comments

Comments