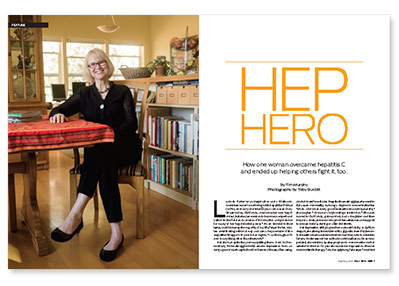

Lucinda Porter is an inspiration and a lifeline to countless Americans living with hepatitis C virus (HCV). Not only did this 61-year-old nurse from Grass Valley, California, overcome her own hep C ordeal, but she also went on to become an expert and author in the field and a source of information and guidance for many of her hep-infected peers. “I’m so devoted to this issue, and it takes up the majority of my life,” says Porter, who is a contributing editor at Hep and also a key member of the Hepatitis C Support Project in her region. “I can’t imagine I’ll ever do anything other than this work.”

But she had quite the journey getting there. Born in Connecticut, Porter struggled with severe depression from an early age and was hospitalized for it several times, often using alcohol to self-medicate. Despite those struggles, she went to Syracuse University, earning a degree in women’s studies. “Then I did what every good feminist in the mid-1970s did,” she laughs. “I became a high-voltage electrician.” She also moved to California, got married, had a daughter and then became a doula, someone who provides assistance and support to women before, during or after childbirth.

But depression still plagued her—almost fatally. In 1988, in despair, she attempted suicide with a gigantic dose of Tylenol—10 times the dose considered toxic to her liver, which went into failure. Doctors saved her with a blood transfusion. Once recuperated, she went to a 12-step program to overcome the alcohol use she’d relied on for years to numb her depression. She also recommitted to therapy. “I had an epiphany,” she says. “I realized I couldn’t even kill myself, so I was going to have to start to live. Something greater than me was saying there’s a reason for you to be alive, even though I didn’t know what it was.” But she took a step: With her husband’s support, she went to nursing school, earning her degree a few years later.

But two months after her lifesaving hospital transfusion, she found herself chronically exhausted. “Then I started to turn yellow,” she recalls, “and they ran some tests, finding elevated liver enzymes.” Her doctors told her they thought that she’d contracted a non-A, non-B form of hepatitis from the transfusion. (It was right before researchers discovered the hepatitis C virus in 1989.) “The doctors told me to go home, don’t worry about it, no big deal, have a lovely life. Which I did, until, in nursing school, they started talking about hepatitis C. I’d previously not given my own hepatitis a thought. But one of my first patients in nursing school was a 35-year-old woman with hep C and alcoholic cirrhosis. I watched her die and I thought, I don’t think this is a benign problem after all.”

By this point, 1995, Porter returned to the doctor and asked for the test to detect hep C that had come out three years earlier. Sure enough, she had it. But she did not freak out. “Once you’ve been close to death, you tend to take news pretty well,” she says. Porter underwent interferon treatment. “It wasn’t fun,” she recalls. “I was quite depressed”—depression being a common side-effect of interferon—and that was scary because I hadn’t been depressed in a while.” She also had extreme fatigue, no appetite and very itchy skin. And, like many hep C patients at that time, she did not clear the virus. (In the past year or so, treatment outcomes have improved dramatically, as have the treatments themselves.)

But something good came out of the experience. “It spurred me into thinking there should be a support group for patients going through this—and there was no such group in my area,” Porter says. “And that’s what got me into hep C activism.” With another nurse, she started a support group. At the same time, she read about a man named Joey Tranchina who’d started an illegal needle exchange nearby to prevent HIV and hep C among injection drug users. “He had gotten arrested, and I thought that was appalling.” After the jury acquitted Tranchina, Porter contacted him and ended up working at the needle exchange in 1997. “Every client there had hep C,” she recalls. “I could see we had a problem and it was bigger than anything talked about on the Internet,” which was still in its infancy as a popular information medium. Shortly after, Porter was among those who started a regional Hep C Task Force.

She then joined with Alan Franciscus to start the Hep C Support Project. At a conference they organized for health care providers and hep C patients, Porter was offered a job in Stanford University’s new liver disease department. She ended up working there until 2008, almost exclusively with hep C patients in studies. “I would teach them how to administer their meds and handle their side effects,” she says. “It was a wonderful job.”

She then joined with Alan Franciscus to start the Hep C Support Project. At a conference they organized for health care providers and hep C patients, Porter was offered a job in Stanford University’s new liver disease department. She ended up working there until 2008, almost exclusively with hep C patients in studies. “I would teach them how to administer their meds and handle their side effects,” she says. “It was a wonderful job.”

But there was still the matter of her own uncleared hep C. In 2003, she did 48 weeks of treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin, which caused her agitation and anemia as well as lightheadedness and fatigue. “But when the going gets tough, I get obstinate,” Porter says. She continued to work and travel and speak nationally, plus make herself walk a couple times a day. Short naps throughout the day, an antidepressant and her support group really helped. “You realize that everyone else is going through what you are,” she says. “When you put it out in the open and laugh about it together, you don’t get scared. It’s gallows humor!”

Though her hep C viral load went to undetectable while she was on the treatment, it rebounded once she stopped. Once again, treatment had failed to clear her virus. “I was still proud of myself for trying,” she says. The experience inspired her to write a book about every aspect of living with and treating the virus, Free From Hepatitis C, published in 2011. (She followed it up in 2013 with Hepatitis C Treatment One Step at a Time—and she’s working on another book, about getting through health problems in general.)

Finally, last year, Porter joined a clinical trial at Stanford and was put into a group getting 12 weeks of ribavirin plus the then-experimental drugs sofosbuvir (now on the market as Sovaldi) and ledipasvir (the drugmaker Gilead has recently applied to the FDA to market a pill coformulated with Sovaldi and ledispasvir). She cleared the virus by the fourth week, with her viral load plummeting from 8 million to a mere 52 in the first week alone. Side-effects-wise, says Porter, “I wouldn’t call it a walk in the park, but with no interferon in the mix, it was my easiest treatment so far.” Porter has been hep C-free ever since.

But if you think that means she’s walking away from hep C advocacy, think again. In addition to her ongoing work for Hep magazine and the Hep C Support Project, she’s still intensely involved in online forums on Hep’s website, Facebook and elsewhere. “My life is heavily hepped,” she jokes. “If there were a psychiatric designation for someone who is clearly a hepaholic, I’d be it.” Nothing will stop her from telling everyone she meets about hep C. “I play my own version of Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon,” she says, referring to the game in which you try to link celebrities to their connection with the Footloose star, in as few degrees as possible.

“I see how soon can I start directing nearly any conversation to hep C,” she says, “because our medical establishment has done a very poor job of screening people for it, especially baby boomers.” They are at risk because they often had transfusions before blood started being screened for the virus in the early ’90s. “We should be screening anyone at risk for hep C, including anyone born from 1945 to 1965,” she says, echoing regulations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). She also wants to see action on the Viral Hepatitis Testing Act of 2013, which would greatly expand hep C surveillance, awareness, testing and linkage to care. “It’s hung up in Congress,” she laments. “Meanwhile, lots of doctors are reluctant to even test patients because they can’t connect them to care, since many states are not advancing affordable health care. But,” she says, “you can at least do antibody testing and confirm that people don’t have hep C.”

Porter has clear and compassionate advice for those just finding out they have hep C:

- Don’t be scared, because fear just makes it worse! Let go of the fear and start getting good info and support. Visit hepmag.com for more information.

- Find a good doctor. Search the American Liver Foundation website at liverfoundation.org or call 800-GO-LIVER (800-465-4837).

- Don’t drink alcohol!

“New drugs are coming out this fall,” Porter says. “They’re worth waiting for. Few people have to be treated immediately, so start by sitting down and learning your options. And know that, despite the appallingly high prices of the new drugs, the drugmakers really are trying to help with patient assistance programs.”

Believe it or not, Porter finds time for a few things other than hep C advocacy. She jazzercises daily and does strength training three times a week. She and her husband travel frequently and are committed to eating local, organic food. “We just made a quinoa dish with black beans, avocado, cilantro, tomatoes and olive oil on a bed of baby kale, and it was delicious!” she raves. She also loves the TV show Mad Men. The secretary-turned-copychief Peggy Olson is her favorite character. “She encapsulates what it’s like to be a female in a male profession,” says Porter, who was once the only female electrician among a crew of men. “They’d try to make me uncomfortable, grabbing my breast and putting snakes and bugs in my lunchbox,” she recalls. “I had to be twice as good as the guys.”

Believe it or not, Porter finds time for a few things other than hep C advocacy. She jazzercises daily and does strength training three times a week. She and her husband travel frequently and are committed to eating local, organic food. “We just made a quinoa dish with black beans, avocado, cilantro, tomatoes and olive oil on a bed of baby kale, and it was delicious!” she raves. She also loves the TV show Mad Men. The secretary-turned-copychief Peggy Olson is her favorite character. “She encapsulates what it’s like to be a female in a male profession,” says Porter, who was once the only female electrician among a crew of men. “They’d try to make me uncomfortable, grabbing my breast and putting snakes and bugs in my lunchbox,” she recalls. “I had to be twice as good as the guys.”

Today, Porter has put that gumption into her mission to take shame out of the hep C equation. “One of the most painful parts of having the disease is the stigma,” she says. “It’s important that we tell our stories and put a face on it to fight that. People say it’s a drug users’ disease, which horrifies me because it stigmatizes drug users and gets us stuck in the wrong conversation. I hope we can get past how people got hep C and focus more on what we’re going to do about it.”

Visit the Hep Bookstore to purchase a copy of Hepatitis C Treatment One Step at a Time or Free from Hepatitis C: Your Complete Guide to Healing Hepatitis C.

1 Comment

1 Comment