Syringes designed to have less “dead space,” retaining a smaller amount of fluid after the plunger has been depressed, could help stem the HIV and hepatitis C epidemics among the world’s 16 million injection drug users, The Atlantic reports. Reviewing the available evidence on the topic, investigators published a review in The International Journal of Drug Policy and used the platform to advocate for wider use of low-dead-space syringes, even before the completion of rigorous—and likely expensive—studies for which they also advocate.

Syringes designed to have less “dead space,” retaining a smaller amount of fluid after the plunger has been depressed, could help stem the HIV and hepatitis C epidemics among the world’s 16 million injection drug users, The Atlantic reports. Reviewing the available evidence on the topic, investigators published a review in The International Journal of Drug Policy and used the platform to advocate for wider use of low-dead-space syringes, even before the completion of rigorous—and likely expensive—studies for which they also advocate.

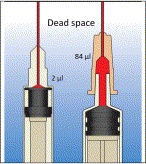

High-dead-space needles retain fluid in the tip of the syringe, hub of the needle and in the needle. Low-dead-space needles, on the other hand, do not have a detachable needle, and after the plunger is fully depressed they only retain fluid in the needle. On average, low-dead-space syringes retain only 2 microliters of fluid, compared with 84 microliters in high-dead-space syringes.

Laboratory experiments simulating injection drug use followed by a rinse of the syringes with water have found that low-dead-space syringes retain 0.1 percent of the blood compared with high-dead-space syringes. The study authors write that, following injection into someone with a viral load between 2,000 and 1 million, the high-dead-space syringes could carry “multiple copies of HIV,” while the “low-dead-space syringes would retain even a single copy only a fraction of the time.”

The authors also cite a recent laboratory study that suggested low-dead-space syringes could help curb the hepatitis C epidemic. In the study, hep C could survive for only one day in a low-dead-space syringe, but for up to 60 days in a high-dead-space syringe.

To read the Atlantic report, click here.

To read the study, click here.

Syringes With Less ’Dead Space’ May Reduce HIV and Hep C Transmission

Comments

Comments